May Month in Review, Chronology and Current Political Prisoners list

Month in Review

●●●

May in Numbers

Arrests: 44

38 anti-war protesters were arrested this month. Six land rights activists were also arrested.

Charges: 49

43 people were charged this month for their involvement in anti-war protests across the country. 22 were charged under Section 19 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act (PAPPA). 18 were charged under Section 20 of PAPPA. Two were charged under Section 500 of the Penal Code for alleged defamation of the Military during a rally. One man was charged under both Section 19 of PAPPA and Section 500 of the Penal Code.

Six land rights activists were also charged this month. Three were charged under Section 20 of PAPPA. The other three were charged under Section 332 of the Penal Code.

Sentences: 41

33 farmers were sentenced under Section 447 of the Penal Code for cultivating their seized land in Mandalay four years ago. Three anti-war activists were sentenced under Section 19 of PAPPA in Mandalay. Two anti-war activists were sentenced under Section 19 of PAPPA in Kachin State. Three people were sentenced under Section 17 (1) of the Unlawful Associations Act in Arakan State.

Releases: 49

33 farmers were released after receiving their sentencing this month. Three people had the charges against them dropped and were released conditionally. Five people in Shan State were released after completing their two year sentence. Two people were released in Kachin State. Six ethnic minority civilians in Shan State were also released.

Prisoners in ill health: 2

Two prisoners are reported to be in ill health.

●●●

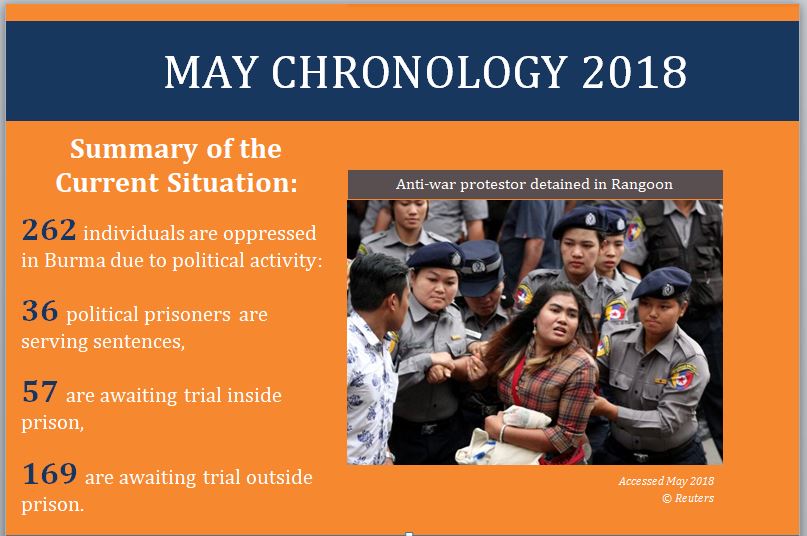

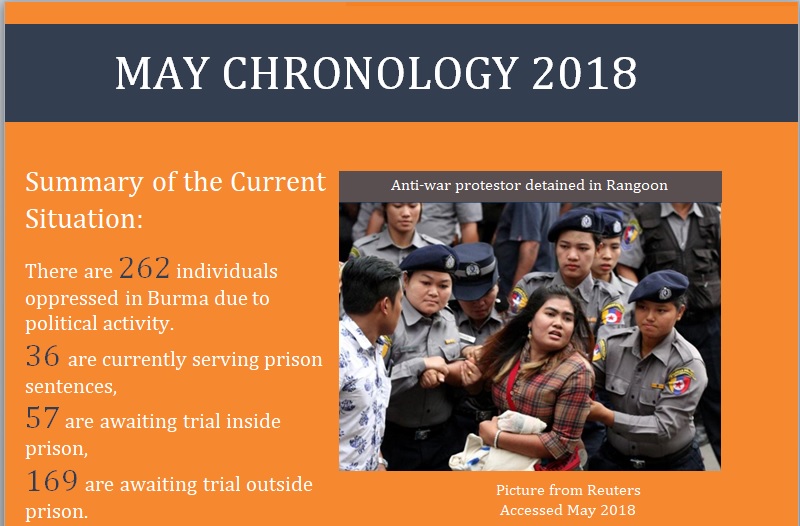

Anti-War Protests Rage across Burma

This month has seen civilians across Burma unite in protest against the renewed Military offensive in Kachin State. Anti-war demonstrations ignited in Myitkyina on April 30, when thousands took to the streets to demand humanitarian aid and rescue operations for people trapped by the fighting, along with an end to the decades-long conflict. The protests quickly spread across the country, with shows of solidarity flaring up in Rangoon, Mandalay, and Bago Region.

The Government initially refused to negotiate with protest leaders and cancelled meetings to discuss their demands. However, the momentum of the rallies quickly grew into a mass movement. After a week of civilian mobilization, the National League for Democracy (NLD) backpedaled and dispatched the Minister for social welfare, relief and resettlement to meet with the organizers, and on May 7, around 150 trapped internally displaced persons (IDPs) were allowed passage to safety despite objections from the Military.

However, without taking away from this accomplishment, the rescue of 150 civilians must be understood in the context of approximately 120,000 people who have been displaced in Kachin State since the ceasefire agreement between the Military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) broke down in 2011. The lack of political will to seriously consider any long-term and large-scale improvements to the humanitarian conditions of the vast majority of Kachin IDPs exposes the assistance provided in May as an underwhelming strategy to appease protesters and counteract increasing international criticism of the Military offensive.

●●● The Government has spent far more resources on arresting and charging anti-war activists than providing humanitarian relief to Kachin IDPs. ●●●

Not only this, but despite its efforts to publicize the meager rescue operation, the Government then spent far more resources on arresting and charging anti-war activists than providing humanitarian relief. Examples abound. In Myitkyina, a planned sit-in rally was thwarted by police at the last minute. Even though organizers had received permission to hold a lawful, non-violent protest, as the group started to assemble at the site the State Government issued an order dated from the previous day stating that the permit had been rescinded. In Rangoon, organizers planned to march from Tamwe to the city’s downtown area but, although they had followed the correct procedures of informing authorities of their plans, they were told shortly before the protest that permission for the event had been denied. In Rangoon, two people collecting donations for IDPs in Kachin State were arrested for allegedly organizing a protest without prior permission. They had not applied for permission as they believed it was not required for such activities. Meanwhile in Pyay, ten more anti-war protesters were detained.

In total, 43 people were arrested and/or charged for their participation in the anti-war movement in May. The vast majority – 41 – were charged under Sections 19 and 20 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act (PAPPA). Also, three people* were charged under Section 500 of the Penal Code for alleged defamatory comments made during a rally. These charges and arrests represent the latest in the State’s frequent attacks on the right to freedom of assembly and association. First and foremost, AAPP joins the multitude of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and activists in calling for the unconditional and immediate release of all anti-war protesters arrested, charged, or sentenced this month. It is inexcusable that those struggling for peace are criminalized by those who claim to champion democracy.

*One person charged under Section 500 of the Penal Code was also charged under Section 19 of PAPPA.

Why Does the Right to Protest Matter?

Enshrined in Article 11 (the right to freedom of assembly and association) of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, the right to protest ensures that the voices of those who often go ignored in Government narratives have a space to be heard. Protests are where ordinary people from all walks of life can find strength in solidarity. They create spaces for open debate, where ideas that diverge from ruling ideologies can manifest and spread. It is through this free flow of ideas that people can recognize their collective power not only to resist oppression, but also to shape the future of society in their own image. For this reason, protests are fertile ground for building strong, united resistance that can bring about massive change in society.

It appears that the national reconciliation process is grinding ever closer to a halt. The rapid spread of anti-war protests this month illustrates the growing disillusionment and discontent with a Government that promised it would place peace negotiations at the forefront of its policies back in 2016. Despite the NLD’s verbal commitments to democratic values, Military offensives continue across the country, basic human rights are attacked on a daily basis, and criticism of repressive policies is violently shut down. Meanwhile, peace efforts at the parliamentary level remain uncertain. Only this month, the Pangalong peace conference, which was created to encourage negotiations between ethnic minority organizations and the Military, was delayed for the fourth time. The Government’s unfulfilled promises leave much to be desired.

●●● The NLD’s unfulfilled promises reveal that, aside from being elected, the Government is democratic in name only. ●●●

Violently cracking down on protesters, rather than taking note of their concerns, only adds to the growing doubt as to the extent of the Government’s intentions to truly bring peace and democracy to Burma. The country is at a crossroads, but while the remnants of authoritarian rule remain steadfast, the only society that can grow is one cast in a similar mold to its predecessor, shaped by those who already have the power to shout the loudest. To prevent this from happening, it is essential that people are not scared into silence, and actively fight for the creation of a democracy which serves the many and not the few. With the stakes so high, protecting the right to protest during this pivotal stage is arguably more important now than ever.

PAPPA: A Toolkit for Repression

The repression of anti-war protesters this month was primarily carried out with an effective legal tool often used to smother dissenting voices in the political arena. The Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act (PAPPA) has been used to bring charges against 353 people for engaging in political activity since its creation in 2011. Consequent amendments made to the Act in 2014 and 2016 have done little to halt these attacks on basic freedoms. This month’s charges in particular provide an ugly exhibit of the range of ways in which PAPPA may be used not only to prevent protests from happening, but also to arrest protesters and organizers at perfectly legitimate gatherings for which permission has been granted.

Of particular concern for AAPP are Sections 19 and 20 of PAPPA. Section 19 has been the Section most commonly used to charge protesters since the law’s latest amendment in 2016. This month, 23 out of 41 anti-war protesters who received charges under PAPPA were charged under Section 19, while the other 18 were charged under Section 20.

●●● Section 19 of PAPPA is the Section most commonly used to charge protesters since the law’s latest amendment in 2016. ●●●

Section 19 of PAPPA, amended in 2016, stipulates that:

“If it is evident that a person found conducting a peaceful assembly or a peaceful procession without notifying according to Article 4, one shall receive an imprisonment sentence no longer than three months or a fine of no more than thirty thousand kyat or both. If a person found committing the same offense recurrently, one shall receive an imprisonment sentence no longer than one year or a fine of no more than one hundred thousand kyats or both.”

PAPPA has a number of rules that must be followed in order for Section 19 to not be invoked. This includes Article 4, which states that “citizens or entities who want to exercise peaceful assembly and procession rights shall inform in written form to the competent township police officer at least 48 hour hours before the intended day”. Alongside the notification, information regarding the location, venue, purpose, date, route, agenda, number of participants and contact details of organizers all need to be provided.

Section 20, meanwhile, stipulates that:

If it is evident that a person found violating article 8, 9, 10, one shall receive an imprisonment sentence no longer than a month or a fine of no more than ten thousands kyats or both. If a person found committing the same offense recurrently, one shall receive an imprisonment sentence no longer than three months or a fine of no more than thirty thousand kyats.

Article 10, which is referred to in Section 20, is particularly problematic. It includes eleven rules that must be obeyed by those participating in a peaceful assembly or procession. For example, participants must not:

- “Cause disturbance to public, public nuisances, endangerment, harm of coercible verbal and physical behavior ” (a);

- “say things or behave in a way that could affect the country or the Union, race, or religion, human dignity and moral principles” (d);

- “spread incorrect news or incorrect information” (e), and;

- “Use loudspeakers other than the approved handheld ones… recite or shout chants other than the ones informed” (g).

Analysis of PAPPA

International human rights law stipulates that any restriction on the right to protest must adhere to the so-called three-part test (see page 32 here); it must be necessary and proportionate, it must pursue a legitimate aim, and it must be provided for by law. The rules in Article 10 – particularly those listed above – are representative of how PAPPA does not comply with these standards.

Firstly, their wording is incredibly vague. Sweeping phrases, such as “say in a way”, “behave in a way”, and “could affect” encompass a huge range of behavior. Leaving specificities as to their true definitions open to interpretation invites their arbitrary application. Further, merely causing “disturbance” to an individual should never constitute grounds for criminal liability. Indeed, it is inevitable and must be tolerated to a certain degree for a protest to have any influence. It is important to note that freedom of expression is not just another right, but one of the primary and most important foundations of any democratic structure (see page 84 here). It is therefore essential to prioritize this freedom over the relatively minor disruptions that may be caused by a protest.

●●● Merely causing “disturbance” to an individual should never constitute grounds for criminal liability. ●●●

Another issue with vague terms such as spreading “incorrect news” or “incorrect information” is that their subjectivity enables them to be used to justify actions taken by authorities to stop a protest simply because they do not agree with its message. This is in direct contrast with international standards, which state that the right to peaceful assembly includes expressing ideas that may not be favorably received by the Government or the majority of the public (see page 15 here). Further, freedom of expression is applicable to information or ideas that are not only regarded as inoffensive, but also those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.

As well as its vague wording, the content restrictions in Article 10 (g) are also impermissibly broad, and open the door for Government censorship of the messages communicated during assemblies. The requirement that details regarding the content and chants of protests are shared with authorities before permission is granted has no place in a democratic society. The only situation in which content-based restrictions may be legitimate is if a protest’s messages are intentionally promoting hate speech or inciting and advocating for imminent violence.

It is worth noting that broad terms such as those found in Article 10 are characteristic of the whole of PAPPA. Further, PAPPA is only one example of a range of deliberately vague laws used in Burma to repress freedom of expression and the right to assembly and association.

Recommendations for PAPPA

Numerous amendments must be made to bring PAPPA in line with international standards, while some provisions must be scrapped altogether. AAPP reiterates its calls for the Government to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a recommendation which it accepted during the November 2015 Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the UN Human Rights Council. The State must implement the below changes to PAPPA alongside committing to its international human rights obligations in order for real reform to occur and for the State to hold any genuine credibility as a true democracy. While these obligations go ignored, repressive laws will only continue to be used to stifle the rights of civilians for speaking out. With this in mind, although Burma is yet to ratify many of them, the below recommendations are based upon the standards laid out in international human rights mechanisms such as the ICCPR.

●●● The State must implement changes to PAPPA alongside committing to its international human rights obligations in order for the State to hold any genuine credibility as a true democracy. ●●●

To begin with, rather than anticipating risks and permitting the criminalization of protests, the Government must reform PAPPA so that a presumption in favor of the rights to freedom of expression, protest and assembly is established. This would ensure that the focus of law enforcement authorities remains on facilitating protests rather than restricting them. With special regards to Section 19 of PAPPA, AAPP recommends that the Section be reformed to erase criminal liability for offenses that do not comply with international human rights standards. Finally, we ask that vaguely worded provisions, especially those relating to dispersal and content restrictions on protests, are revised to ensure that they are sufficiently specific according to international standards.

A Step Backwards

Rather than seeking to address the shortcomings of PAPPA, the Government is currently veering in the opposite direction. An amendment already passed by the Upper House in March 2018, and currently under debate in the Lower House, would lead to even more restrictions being placed on protest organizers as well as longer prison terms and unlimited fines (see AAPP’s March 2018 Month in Review here).

The efforts to steer PAPPA even further away from conforming to international standards is extremely concerning, and not without a hint of irony. In strengthening the same laws that were used to repress many of its MPs during the Military dictatorship, the NLD’s actions only add to suspicions – already heightened this month after the brutal anti-war protest crackdowns – that its democratic ideals are more of a political facade than a true commitment. While the Government’s complete disregard for the rights of its civilians remains, Burma’s abidance to the norms of tolerance and democratic paradigms will only be constrained to the realm of theory.

●●● While the Government’s complete disregard for the rights of its civilians continues, Burma’s abidance to democratic paradigms will only be constrained to the realm of theory. ●●●

However, it is important to note that despite its seven year existence, PAPPA has not entirely prevented protests from taking place. The courage of those who were prepared to face imprisonment this month for demanding peace is commendable, and is just one example of the spirit of resistance that has marked decades of Burma’s political history. Notwithstanding the divides in the country, the widespread solidarity seen in the anti-war protests is cause for optimism. As the authorities continue to file charges and push through legal amendments in an attempt to silence protesters, the movement has only added kindling to a deep-rooted flame of resistance that no amount of repressive laws will be able to extinguish.

Peaceful Protests and Violent Police

Not only did authorities use PAPPA and other laws to suppress anti-war protests this month, but they also resorted to physical violence. In Rangoon’s Tamwe Township, protesters were forced to disperse after police declared that permission to hold a march had been denied. The organizers agreed to leave, but as they were dispersing police and men in civilian clothing stormed the crowd, beating and violently arresting protesters.

The fact that Burma’s police are still upholding their militaristic reputation of attacking their own citizens rather than maintaining law and order is an insult to the values of fair, democratic rule. Moreover, it is not the only similarity that can be drawn between the police’s behavior this month and the brutal repression by state security forces seen in past governments. Reports soon emerged that plainclothes officers and civil groups assisted the police in scaring, attacking, and arresting protesters. Whether they were directly employed by the police or not, evidence that police officers passively watched on as these individuals beat protesters is completely unjustifiable. Media outlets later claimed that some of the men were recognizable as nationalist and pro-Military supporters. If this is true, the fact that police is actively aligning itself with such groups would expose the influence that militant views still hold over their policies. This is inexcusable for an institution which must remain non-partisan and objective in order to carry out its duties in a fair and just manner.

However, the parallels that can be drawn between the police tactics observed this month and those from the Military dictatorship are hardly surprising, considering that Burma’s police force is part of the Military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs. For any fundamental reforms to take place within the police force, it is imperative that control of the police is handed over to the Government so that it is under civilian authority. Efforts to reform without a handover of control will ultimately be piecemeal in nature, such as a 30 million euro project launched by the EU in 2016. Despite aiming to train Burma’s police force to adhere to international standards and respect human rights, the five-year project appears to have had little effect so far, as May’s events demonstrate, and has been subject to repeated criticism.

●●● For any fundamental reforms to take place within the police force, it is ultimately imperative that control of the police is handed over to the Government. ●●●

Rather than simply relying on international aid, AAPP calls on Burma’s authorities to take responsibility for much-needed police reforms, which should follow the immediate transfer of police control to the elected Government. While the chain of command remains unchanged, the boundaries between the police, the Military, and “community groups” will remain ambiguous, sapping credibility from the police force as an independent and objective institution. In short, there cannot be any faith in the rule of law while law enforcement agencies themselves show no respect for it. With regards to the reports of plainclothes individuals beating and arresting protesters this month, AAPP is encouraged by the promise made by chief Police Brigadier-General Aung Win Oo to investigate the allegations. We emphasize that these investigations must be immediate and independent, and carried out with a view to ensuring that the perpetrators of violence do not enjoy the cover of impunity. They must also bring transparency to the nationwide issue of the unlawful use of civilians by police to repress protests. Until these steps are taken, its image will no doubt remain tarnished while its brutal and repressive tactics will continue unabated.

Military Accused of Torture and Murder

State violence has not been limited to the police force this month. Military officials have also been accused of committing shocking human rights abuses across the country, including torturing and murdering civilians. In Mawkmai Township, Shan State, four male residents were beaten by the Military’s No. 430 Light Infantry. Officers approached the men while they were herding buffaloes and accused them of associating with an Ethnic Armed Organization (EAO). They then proceeded to cut one man’s ear off and crack another’s skull. Further, a civilian in Rathedaung Township, Arakan State was beaten by two unknown soldiers. Two of his teeth were broken. Another civilian working on Kalagoke Island in Ye Township, Mon State was beaten and murdered by a Military Captain after being taken away for questioning about his NRC card.

Torture and murder are recognized as some of the worst human rights abuses. Both EAOs and the Military are most often accused of committing such atrocities, yet despite the extensiveness of the pandemic, the perpetrators often enjoy complete impunity. The authorities’ failure not only to prevent such violations, but also to hold those responsible to account, only encourages their continuation. Although the previous nominally quasi-civilian Government led by Thein Sein made a commitment to sign the UN Convention against Torture (UNCAT), the treaty is still missing Burma from its list of signatories. AAPP reiterates that the Government must sign and ratify the UNCAT without delay. Until the State shows that it is making concrete efforts to tackle the rampant allegations of torture across the country, any promises that it is working to improve the security and enjoyment of human rights for Burma’s citizens can only ring hollow.

Prison Reforms Eclipsed by Overcrowding and Torture

This month, it was announced that a Youth Centre in Mandalay will provide a vocational education course for 120 young people. These are encouraging – and essential – steps forward with regards to prison reform, enabling young people to restart their lives and to positively participate in the community after their release.

However, shocking reports have also emerged concerning the torture of minors detained with adult prisoners. After conducting interviews with children, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission (MNHRC) found that of those detained with adults, many children are beaten and kicked by police officers on duty. Detaining children with adult criminals and subjecting them to physical torture is abhorrent, even more so in a supposedly democratic society. AAPP is extremely concerned that reports such as these are still emerging two years after the NLD came into power. They not only reveal that basic human rights continue to be completely disregarded in Burma’s prisons, but they also raise doubts as to the true extent of the Government’s commitment to prison reforms such as those detailed above.

●●● AAPP is extremely concerned that reports of torture in prisons are still emerging two years after the NLD came into power. ●●●

The Government should not need reminding that no child or adult shall be subject to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, according to the Section 37 (1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), or that these rules also extend to those who are detained or imprisoned. Under no circumstance whatsoever is torture justified. Burma signed the CRC in 1991, and so the State is legally obligated to respect and follow its guidelines. Additionally, young prisoners must be kept separate from adults, according to the OHCHR rule no.8 (d). AAPP therefore not only urges the Government to follow these rules and treaties, but also calls on the Government to train prison staff in adhering to human rights standards as well as working to increase the understanding and effective application of the rules stipulated in the CRC in prisons.

Along with allegations of torture, overcrowding continues to be a growing issue in Burma’s prisons. An inquiry into human rights violations in Dawei Prison also carried out by MNHRC this month revealed that the prison, built to hold 500 prisoners, is currently over capacity by approximately 200 prisoners. Furthermore, prisoners do not have enough space to sleep and cannot take proper showers. AAPP’s 2016 report on prison conditions and the potential for prison reform in Burma details the devastating effects that overcrowding can have on sanitation infrastructure and public health in prisons (page 18). Moreover, we would like to reiterate that overcrowding constitutes a form of torture (please see our April 2018 Month in Review for more details). Further, overcrowded prisons create fertile ground for other abuses to occur. Fundamental reforms to the prison system which prioritize the elimination of overcrowding are therefore essential if human rights violations are to be curbed.

●●● AAPP reiterates that overcrowding constitutes a form of torture. ●●●

Burma’s domestic law includes provisions against overcrowding in prisons. Article 7 of the Prisons Act states that if the number of prisoners is over that deemed convenient or safe, provisions shall be made for the shelter and safe custody in temporary prisons for those prisoners who cannot be safely or conveniently kept in the prison. The Jail Manual provides more specific details as to the definition of what the Government deems “convenient and safe”, but its provisions fall short of international standards (more information can be found on pages 18 and 19 here). In particular, The Handbook on Strategies to Reduce Overcrowding, a joint publication between the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC), contains specific guidelines regarding the definition and prevention of overcrowding in prisons. Subsequently, the Government is not only obligated to address overcrowding under international standards and procedures, but also according to its own domestic law. AAPP therefore urges the Government to take immediate action to resolve prison overcrowding and the plethora of other human rights abuses that it entails.

Land Protests and Repression Unremitting

In May, land protests and disputes continued unabated. Farmers’ lands are often confiscated by the Government, Military, EAOs, and private corporations with either very little or no consultations or compensation offered. Left landless and unable to make a living, charges and sentences the add insult to injury for farmers who dare to protest the seizures or attempt to continue cultivating their confiscated lands. This month is testament to the numerous ways in which farmers are forcibly suppressed, shot and tortured simply for defending their rights.

On May 12, farmers living in the Thilawa Special Economic Zone in Kyauktan Township protested against the pitiful compensation provided for land seized by the Military company Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) in the mid-1990s. Despite a long battle for justice, the company is still refusing to hold negotiations with farmers. Police brutally cracked down on the protest and opened fire on the crowd, injuring two civilians and arresting another three.

On May 14, the Mong Tai Army (MTA), responsible for seizing over 300 acres of land from farmers in Loilem Township, Southern Shan State in 2011, beat, shot and threatened farmers with guns for ploughing in the confiscated land. Although none died, many villagers were injured.

Additionally, land disputes continued this month between Yuzana Company and residents of Nawng Mi Village in the Hukaung Valley Region. Over 100 acres of land belonging to ten farmers were dug up by the company in the second week of May, according to a resident.

Sustained attacks on farmers not only by police but also by EAOs contradict the national reconciliation process and the values of democracy. Moreover, it illustrates the weakness of the civilian Government in adequately resolving land disputes and providing compensation when confronted by the power of those that have seized it. Both the UN’s Basic Principles on the use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement and its Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials clearly lay out strict rules for police and security forces regarding the use of weapons. In particular, force and firearms may be used only when absolutely necessary, after negotiations have taken place and if non-violent means remain ineffective. If they are used, it must only be to the extent required for the performance of their duty and it must always be commensurate with due respect for human rights.

●●● Sustained attacks on farmers illustrate the weakness of the Government in resolving land seizures when confronted by the parties responsible. ●●●

AAPP urges the Government to immediately investigate and address all inappropriate uses of force reported this month in relation to land disputes. Furthermore, rather than attacking farmers for protesting, the Government is legally obligated to act according to Section 22 of its 2012 Farmland Law, which states that “land disputes in respect of the right for farming shall be decided by the Ward or Village Tract Farmland Management Body, after opening the case file and making actions such as enquiry and hearing about the land disputes” (see page 6 here).

Although the Government did return land or provide compensation to farmers in some townships in Karenni State, Mon State, Mandalay Division, Sagaing Division and Magwe Division, farmers from Bago Division, Mandalay Division, Arakan State and Irrawaddy Division were also forced to stage protests to fight for recognition of their seized lands and compensation for their losses.

A case in point, whose sentencing this month was labeled a blow to land rights in Burma, involved 33 farmers ordered to pay fines under Section 447 of the Penal Code for cultivating their seized land in Mandalay four years ago. Even though Articles 7 and 10 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights state that all are equal before the law, all are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law, and that everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing, farmers did not receive a fair trial and were arbitrarily charged and sentenced under a repressive law. This case is just one example which highlights the unnecessarily prolonged trials which many activists must endure for struggling to maintain their livelihoods and protesting against land seizures.

●●● The case of the 33 farmers involved arbitrary charges imposed under a repressive law and a prolonged and unfair trial. ●●●

In addition to unfair and prolonged trials, the decision in the case of the 33 farmers also directly contravenes Article 6 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). These principles state that everyone has the right to make a living by work which is freely chosen or accepted. However, land confiscations rob farmers’ of their ability to make this choice. Furthermore, Article 1 (2) of the ICESCR stipulates that “in no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence”. Therefore, AAPP calls on the Government to immediately retract its sentencing of the 33 farmers this month, as well as making the resolution of land issues a top priority due to their devastating effects on farmers’ livelihoods throughout the country.

The continuation of land seizures and unjust sentencing into the present ensures that restrictions on land rights remain a steadfast obstacle inhibiting the success of the national reconciliation process. While there are no acknowledgements, apologies, or reparations for past land seizures, and while farmers and villagers are still targeted for defending their rights to livelihood and land, the democracy achieved through the transition process will prove little different from its predecessor.

Repression under the Unlawful Associations Act Continues

The Unlawful Associations Act continued to be used to terrorize civilians this month. An archaic law implemented during the colonial era, it is infamous for charging anyone who is accused of affiliating with EAOs, including journalists, villagers and forcibly recruited soldiers. Although 15 people imprisoned under the Unlawful Associations Act were released in the Presidential Pardon in March 2018, in May three more were newly sentenced under Section 17 (1) of the same law for alleged involvement in a bomb blast in Ponnagyun Township.

The Unlawful Associations Act obstructs the possibilities of improving relationships and building trust between EAOs and the Government, both of which are vital to the progress of the national reconciliation process. While this law continues to be used to criminalize and stigmatize EAOs and anyone who is accused of having connections with them, transparent and mutually respectful negotiations will remain a fanciful notion rather than a concrete step to achieving peace.

●●● Section 401 (1) of the Penal Code, which enables re-incarceration even after release, has devastating effects on the lives of former political prisoners. ●●●

May also saw three residents, who had been charged under Section 17 (1) and (2) of the Unlawful Associations Act for alleged ties with the Arakan Army (AA), released conditionally by the Mrauk U Township Court. Although we welcome any release, AAPP condemns the Court’s failure to grant the three men unconditional release. This means that they will continue to face the possibility of being re-arrested under the same Act to finish their sentence. The clause, Section 401 (1) of the Penal Code, that enables re-incarceration has devastating effects on the lives of former political prisoners. AAPP repeats its calls for the Government to remove this clause and to retroactively grant amnesty for all those currently suffering under the constant threat of imprisonment despite having been released. We also call on the Government to withdraw the Unlawful Associations Act in its entirety. It is a repressive and outdated law and has no place in a democratic society.

Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP)

Tate Naing (Secretary) +66 (0) 812 878 751

Bo Kyi (Joint Secretary) +66(0)81 962 8713

Download link for Month in review MiR May Final

Download link for Monthly Chronology may chronologyDownload link for Current remaining PP list 36 Remaining PP list Updated On May 31, 2018

Download link for Facing trial list 226 facing trial list updated on May 31, 2018 (Updated)

Download link for 66(D) list 66 (D) total list(new) Updated